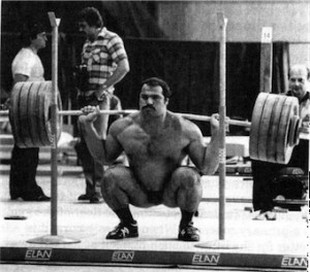

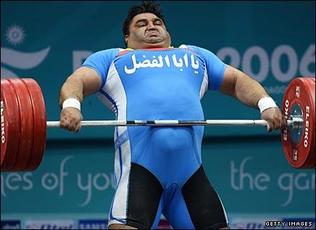

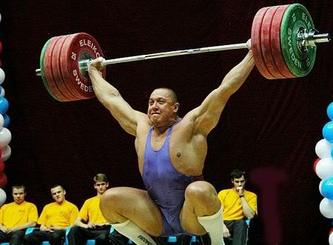

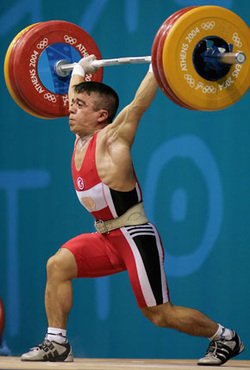

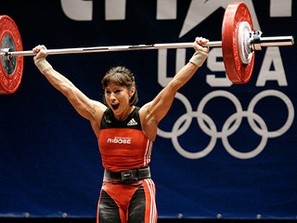

I am a fan of olympic weightlifting for many reasons, and I may have an affinity to train many of my athletes with this style of training. However, I realize not all athletes are ready for the full competition lifts immediately when they begin their training. Moreover, the full competition lifts really are not necessary for general athletes. On the contrary, a foundation of simpler exercises is going to be much more beneficial for the novice and intermediate trainee. Once the athlete has developed a solid foundation of the most basic strength building exercises, they should gradually add slightly more complex movement patterns to their training over time. Adding these movement patterns will likely be a weekly or monthly process, not a daily one. Never be in a rush to increase the complexity of an athletes training, but increase the effectiveness of keeping things as simple as possible for as long as possible. There really isn't any need to try to invent new exercises, everything you need to know is already full public information. But it is hard to make a name for yourself as a coach by doing what has already been done. So, many coaches try to reinvent the wheel by making up new exercises that can only be described as silly instead of effective. Heed the following simple advice: don't reinvent the wheel, just get better at using the wheel.  Before I begin utilizing the competition lifts (snatch and clan & jerk) or their variations with my athletes, I ensure that they have satisfactory competency with the basic pillars of strength building exercises and movement patterns. These movement patterns include pushing, pulling, squatting, and hinging. We also need to have a balanced mix of controlled tempo work/isometric holds and dynamic/explosive elements in our training. However, it is imperative that the athlete develop a good amount of strength, stability and mobility before any emphasis on dynamic training takes place. Always practice the rule of simple before complex. Far too often i think some coaches rush to the high intensity drills that they think will yield the best results, but the athletes haven't been properly prepared to benefit from high velocity training. It's like expecting a third grader to benefit from advanced calculus classes. Without being properly prepared to understand the information, there will be no benefit. In the case of weightlifting, if the athlete is not very strong or stable in certain positions, training for speed or power will have little benefit. The answer is to stop chasing excessive variety and entertainment in training, and focus on getting stronger. Basic strength is the foundation for all physical training. Especially in the early stages of training, getting stronger will carry over to all other aspects of athleticism. But random fun workouts without a progressive goal will have less benefit for the athlete. I find it most helpful during the learning phase to introduce the movements in small pieces which isolates a relatively small range of motion of the exercise. This helps the athlete realize the importance of proper position before any increase in intensity occurs. So what we do is actually isolate a few small range of movement patterns, then integrate them all into one fluid movement pattern when the athlete is ready to add more complexity to his training. Isolation, then integration. These isolated movements are not necessarily isolating muscles, but are simply minimizing the movement pattern into smaller parts to make it easier for the athletes to learn. When it becomes second nature, you add on the next step. Again, this does not occur in a 5 minute warm up before a high rep workout, but over the course of many weeks. The athlete must have time to learn, adapt, and practice.  After learning how to explode the bar upwards with hang pulls, the athlete needs to learn how to receive the barbell in the rack and overhead position for the clean and jerk and the snatch. This is done with delivery drills like muscle cleans, muscle snatches and push presses. From here, it is simply a matter of gradually adding range of motion and velocity to the given movements, and even adding a second or third movement as a complex to increase agility by transitioning from one movement pattern to another. The muscle clean will eventually morph into a hang muscle clean, then a hang muscle clean plus a front squat, then a hang power clean, then a hang squat clean, then a low hang clean, then a clean from the floor. Very similar drills can be applied for the snatch, the only difference is where the athlete receives the bar. Instead of front squatting for the clean, the athlete can perform overhead squats to improve stability in the bottom position of the snatch with the barbell overhead. But nothing will help the power of the snatch more than the Olympic style back squat, in my opinion. Again, these progressions are not introduced over the course of minutes or even days in some cases, but over the course of several weeks or months. It is all a very individual circumstance, depending on the quality of movement from the athlete. My basic answer for when it is appropriate for an athlete to progress to the next complex exercise is, "when it's easy". However, if the athlete is truly "getting it", a session or two at one progression may be sufficient before moving forward.  The overhead squat is a great mobility drill and also develops good core strength and confidence in beginners by allowing them to feel that position slow and controlled at first. Once the athlete has developed proficiency with over head squatting, they need to learn how to get in to that bottom position with more velocity. A pressing snatch balance is a great drill to introduce the athlete to pushing under the bar, instead of just pushing the bar up. Following the pressing snatch balance, the athlete learns the heaving snatch balance, which begins as a push press and finishes with the athlete pushing themselves aggressively under the bar. Finally the snatch balance is introduced, which is performed with maximal tenacity and velocity. The snatch balance is a serious drill the begins with the bar on the athletes back like a back squat, the athlete dips and explodes upwards generating momentum and elevation on the barbell while immediately transitioning from pushing the bar up to pushing the body down. This drill requires, as well as creates, a lot of aggressiveness and agility. It can not be done timid or slow. Each progression is adding range of motion, increasing velocity, or both.  The jerk is the phase of the lift that has always provided me with the most frustration, pain and problems. I pretty much suck at it, yet it looks to be the most simple of all the Olympic lifts. Its the fastest lift, it has the shortest range of motion, and in theory it should be the easiest. But it is not always the case. It may be simple for some, but nearly impossible for others. I, unfortunately, am one of those athletes that never got very good at jerking, but I will do my best to help you anyway. Starting with the press, the athlete will eventually learn to press behind neck. It requires more shoulder flexibility, but it automatically puts the head and shoulders in the best position to support a heavy load overhead. Dip squats are basically a quick quarter squat, and can be done with the bar on the back or in the rack like a front squat. They introduce speed and aggression on the bar, while maintaining a tall, rigid torso. Next you put the dip squat and the press together for the push press. Incorporating a foot transition drill is good to teach the athlete to move their feet from a pushing position like the start of a clean, snatch, jump or deadlift, and quickly move to a receiving position as in a squat or landing from a jump. You could, and should, also teach a split receiving position, where the athlete receives the bar in a lunge position. This is beneficial for those athletes with less shoulder mobility, but requires more foot speed. There are a few drills you can do to help acquire the necessary speed and aggression to perform the jerk well, like tall jerks or jerk balances. Each of the drills train you to either push down under the bar or transition your feet to an optimally stable position. However, if the athletes are not planning on competing in olympic lifting, these drills may not be all that necessary and may only over complicate the training while providing little benefit for their sport for the time invested in their training. The first phase of the snatch is much like the clean, where you push hard in to the ground and pull the bar up and in to your body. The final phase of the snatch where you transition from pulling under the bar to pushing under the bar, is much like the jerk. This part seems to be a bit tougher for many athletes to grasp. The finish is an extremely aggressive push under the bar, not merely a long pull that lands over your head.  In my opinion, the jerk is the most violent and aggressive movement of the all Olympic lifts, and possibly in all of barbell training in general. Surely there will be many who disagree, largely due to individual strengths and weaknesses. Some people clean more and others jerk more. The balanced athlete will be damn close in both lifts at 100%. Having discrepancies can actually be a good thing, as it provides clues as to how you should structure your training. Bringing up your weakness is more important than perfecting your strengths. I'm not saying you don't need to squat if you already have a good squat, but you'll always be limited by your weak link, so you better get that thing fixed and prioritize your training accordingly. The main reason why I like Oly lifting for athletes so much is because of the integration of all of the natural major movement patterns of our body. The clean and snatch begin by squatting down, grabbing the bar, and pushing your feet into the ground as hard as possible, while maintaining a rigid torso. This dynamic movement of the hips and legs, integrated with an isometric hold of the back, develops superior strength, explosive power and general athleticism. Following the initial pull from the ground, the athlete jumps hard, but not high, because he instantly transitions to pulling his body under the bar. He then pulls the bar aggressively into his body by bringing his elbows high and outside and pulling the body around the bar. There is a powerful hinging movement of the hips that occurs while bringing the barbell up past the thighs, constantly pulling on that barbell. After the jump the athlete then pulls his body down because he is no longer connected to the ground. There is constant tension being applied from the body. The force is either going into the ground as the anchor, or applied to the bar as the anchor, there is never a slack instant during the lift. Once the athlete pulls under the bar and receives the weight in the squat position, he must apply maximal force pushing into the ground to stand up from the squat which puts the hips through a full range of motion, again while isometrically contracting the torso. After standing from the clean, the athlete adjusts, dips and drives the bar upward as aggressively as possible and jumps his feet into a receiving position. While the feet are not connected to the ground, the bar is the anchor and the athlete uses that anchor to push down under that bar as fast as possible. After receiving the bar overhead in the jerk, the athlete must recover by again holding a solid isometric contraction with the upper body while dynamically pushing his legs in to the ground to return to a standing position. There is a perfect blend of pushing, pulling, squatting and hinging, as well as constant use of isometric strength and dynamic strength involved in the olympic lifts. That is what makes it perfect for athletes.  While I think the Oly lifts are great for athletes, if they are all you ever did for your training, you would always be training with full integration. That is not bad, but it is incomplete. Remember, we need isolation and integration. You must isolate each of the movements, the pulls, pushes, squats and hinges, to maximize your strength in each which can be expressed with your Oly lifting as an integrated movement which improves your agility, speed, strength mobility, stability and general athleticism simultaneously. In conclusion we have a few key points. Prioritize strength, mobility and stability in your training, especially early on in the athletes training career to build a solid foundation. Strength and stability is best developed with a barbell using basic exercises like squats, deadlifts and presses. Progressive bodyweight training is outstanding as well, but I'll save that for another article. It makes perfect sense to begin light and progress to heavier weight, but many people lose focus when it comes to training complexity. Always begin with simple movements, focus on mastering the basics, and gradually introduce more complex movements over time. Knowing the progressions is good, but not every athlete needs every progression. Knowing what drill is appropriate for which athlete is the golden ticket. You can't buy that ticket, you must train and learn with experience. The good news is, qualified experience is only 10,000 hours away. So, you better be passionate about what you're coaching or training, because spending that much time doing something you don't enjoy is as fun as an eternal conversation with your annoying ex who made your ears bleed and brain hemorrhage every time she opened her fat mouth. Following a solid program is important, but you need to be smart enough to know when to make adjustments. Be humble, there's going to be a lot of detours on your journey. Injuries, holidays and hangovers are a part of life, and as such, they will take their toll on your training. Enjoy the road, train hard, be aggressive, floss daily and get strong because it's always better lifting bigger weights. But not right away. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed